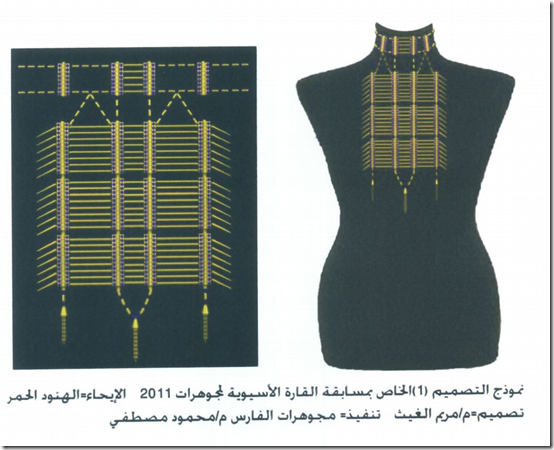

Series of hand-thrown bowls by Andrew Widdis

Senator’s John Madigan and Nick Xenophon recently purchased a range of tableware made in Australia, by Robert Gordon Australia, for the Australian Parliament. “The situation is so dire that in order to get Australian-made goods into our Federal Parliament, Nick and I had to buy them ourselves.”[i] Though it may not be long before Robert Gordon Australia goes completely off shore “some now outsourced to China”[ii]

We fulfil large scale ceramics orders in Australia, at a somewhat competitive price, but we need to raise the Australian consumers attention to what they are buying to make this viable, the federal Government needs to support small business’ that have the ability, but not necessarily the finances to invest on a risky proposition in the current market.

As with Robert Gordon Australia, manufacturers of Australian ceramics don’t seem to survive long solely manufacturing in Australia, but they might find it a little easier if an educated market sought them out because they understood what it takes to make locally. Perhaps one of the easiest and most immediate ways would be in raising awareness and education of the “Australian Made”[iii] logo” by promotion from the various levels of government. This seems to be the easiest way to give some market share back (also removing the need to have a magnifying glass when shopping).

Recent manufacturers in Australia that should have been able to up-scale and compete with imports are perhaps: Elliot Golightly[iv] and Bison Home[v]. I worked for Elliot Golightly in Nth Melbourne; they were going well for a couple of years. They even had a big order from U.S.A. while I was there, but China started copying them and they slowly lost market share and ended up selling the main designs to a tile company in Ballarat. Unfortunately, I don’t think the tile company made much of it.

Bison Home was proudly hand made in Canberra. With orders from Australia’s big retailers, such as Myers, Bison Home have recently started sourcing from O/S, and I assume they make very little in Australia now, if any. Although Brian Tunks’ (owner of Bison Home) health is given as the main reason[vi], he should have had access to change his process in Australia.

So if these people tried to make solely in Australia and failed, it’s not likely that any other manufacturer is going to succeed in Australia. Only small studio/artist set-ups seem to be the go; usually because it is more a ‘lifestyle” than a financially viable proposition.

Anyone with enough money to buy the efficient equipment that would enable them to compete with Asia are more likely to take the safer option of investing that start-up money in importing the product. We simply don’t have a market that cares where a product is made, as long as it’s cheap, is the mentality here. So why take the risk. I’d love to manufacture a commercial range in Australia, and particularly in Regional Victoria (I live in Bendigo, where we have some history in tableware manufacture), but until I feel supported I’m not about to risk it (I started down the road of starting a commercial production, but soon realised it was going to be a losing proposition (I still have a 3 phase pot press if you want to give it a go)). I have no issue with importing generic white-ware from China, it has given everyone access to a cheap strong hygienic product, and it has given a higher income to many throughout Asia; it does not take market share from local studio potters.

With the devastation caused by the “financial crisis[vii] in U.S.A. and Europe; England and U.S.A. have taken steps to begin “reshoring”[viii]. In the U.S.A. American Mug & Stein Co.[ix] have been making the “Indivisible” mug for Starbucks, in Ohio, U.S.A.. It is seen as a sense of pride to support locally made product (you can visit the maker, you can see how it’s made and see the working conditions, etc. Perhaps it’s a logical progression of “slow food.”).

Labour costs are not necessarily an issue. Ceramics manufacture can be highly automated[x] using pot pressing[xi] rather than the conventional factory set up of slip-casting[xii], pot press methods can be completely automated (no need for a person to pour and remove the casting) and they are highly efficient at minimising waste, the clay trimmings are even automatically recycled with some of the latest equipment. With turnkey hand-over solutions available from German industry[xii] providing the latest automated machinery and conveyor belt systems for the ceramic industry. Pressing lines for clay pots/bowls/plates picked up and placed on conveyor belts to the next process step; but it’s a lot of money, and as I suggested, anyone with that money would see the safer option of having to only buy the end product from Asia.

Bendigo Pottery[xiii] continue to make a small quantity in Australia, but its days may be numbered. Last year a quarter of the factory space was turned into an antique stall holders set-up. If that ‘ain’t the writing on the wall…

I have a set of flat plates that have been in service for over 20 years, manufactured in Australia by “Australian Fine China”[xiv]; unfortunately they are now sourced from South East Asia. Previously known as “Bristile crockery” they manufactured vitrified white crockery (made in Western Australia), and often ‘badged’ for Government Departments and other institutions.[xv] So the Australian Parliament did once have more than enough Australian made crockery.

In England the traditional pottery area of Stoke on Trent is a prime example of how a once devastated industry can be turned around, indeed flourish, against the once perceived unbeatable Asia, home of cheap ceramics production. An example of a successful manufacturer in a “high wage country” is Dudson[xvi] using efficient equipment and best work practices including promoting environmental and carbon awareness along with showing pride in a local product by labelling with “Made in England” and having the British Standard 4034 Kitemark for assurance of quality[xvii]. Along with a supportive ethic for local manufacture “Our leading production facilities in Stoke-on-Trent embody a strong commitment to England, sourcing locally wherever possible and nurturing local skills and expertise”[xviii]. Dudson has found strong support from the likes of “Avril Gayne, Hospitality Services and Control Manager at the Eden Project[xix], commented, “It’s not just the origins of our food and the impact on the environment that we are passionate about. What excites us about Evolution” (Dudson’ ceramic hospitality tableware) “is the fact that, like our menus, ingredients are sourced locally whenever possible, supporting the community and keeping carbon production to a minimum.””[xx]

I’m sure we can make a viable “green” tableware product in Australia. The Dudson “Evolution” range is available in Australia; and it seems to be a price that local cafe’ happily pay. I recently had lunch with family members at a new (small) cafe in Surrey Hills (Cocco Latte, 111-113 Union Road, Surrey Hills, VIC. 3127) My Mother commented on the interesting tableware, so I picked a plate up to look at the base (to see who made it), I was surprised/impressed that it said “Dudson” “Made in England”. So if we’re buying a “green” product, but reloading it with carbon by shipping it from further away than Asia; why are we unable to find a way to make a similar product here? An Australian distributor of Dudson proclaims “Evolution has been developed with the prime objective of reducing the carbon footprint created during manufacture”[xxi]

There are many good reasons to start manufacturing ceramics in Australia. Firstly the issue of inefficiencies in getting it here from overseas; energy wasted in trucking/shipping/trucking to your local High Street.

We have all the natural minerals required for the finest porcelains here in Australia, and relevant to me we have them all here in Victoria. Natural gas (we ship it to Asia) etc. Porcelain is made of mainly Kaolin[xxii], with some silica[xxiii] and then feldspar[xxiv] to bring the vitrification point down to a commercially viable temperature (1280°C). I’ve formulated my own porcelain[xxv] and glazes[xxvi] over many years, and I’ve made pure white porcelain from Australian minerals, though I don’t usually use the purest kaolin it can be sourced from a Victorian quarry; the whitest export grade kaolin (mined near Ballarat) is used mainly for coating glossy magazines. It is somewhat upsetting to a potter that these pure white kaolins are not used for a more lasting product.

With the latest equipment from industrially savvy counties like Germany, and making fine white porcelain tableware locally we can value add to our own resources, while at the same time reducing carbon.

Even more efficient equipment than pot press’ are now available. Isostatic press'[xxvi] a technology that requires minimal water in the clay, no hydraulics to ram the die down and no 3 phase motors to spin the dies during compression. This is another massive saving in energy resources.

As well as putting solar panels on roofs and vast arrays in the deserts and clearing bush to make solar parks[xxvii]; putting turbines wherever there’s no danger posed to budgies, why aren’t we also investing in efficient manufacture that use our local resources. Instead of throwing millions of dollars[xxviii] at American cars that guzzle resources, can’t we send some to a production that vitrifies it.

Notes

i http://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/victoria/senators-john-madigan-and-nick-xenophon-splash-out-to-support-australian-crockery-makers/story-fni0fit3-1226699535669

ii http://www.australianpotteryatbemboka.com.au/shop/index.php?manufacturers_id=267

iii http://www.australianmade.com.au/

iv http://www.elliotgolightly.com

v http://www.bisonhome.com

vi http://www.smh.com.au/lifestyle/homestyle/new-life-of-brian-20121127-2a5hh.html

vii http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Financial_crisis

viii http://www.forbes.com/sites/mitchfree/2012/06/27/is-the-re-shoring-of-manufacturing-a-trend-or-a-trickle/

ix http://americanmugandstein.com

x http://www.designboom.com/design/laufen-factory-visit-ceramic-casting

xi http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QlXwoqqwC-I

xii http://www.dudson.com/products/finest-vitrified-tableware

xiii http://www.bendigopottery.com.au

xiv http://store.australianfinechina.com.au/category/list/#/Content/?id=212

xv http://www.wembleyware.org/history-of-the-factory

xvi http://www.dudson.com

xvii http://www.dudson.com/products/finest-vitrified-tableware

xviii http://www.dudson.com/company/manufacturing

xix www.edenproject.com

xx http://www.dudson.com/news/product-news/evolution—the-story-continues-

xxi http://www.southernhospitality.com.au/brands/dudson/dudson-evolution-oval-bowl-pearl-216mm.html

xxii http://www.dpi.vic.gov.au/earth-resources/minerals/industrial-minerals/a-z-of-industrial-minerals/kaolin

xxiii http://www.dpi.vic.gov.au/earth-resources/stone-sand-and-clay/silica

xxiv http://www.dpi.vic.gov.au/earth-resources/minerals/industrial-minerals/a-z-of-industrial-minerals/feldspar

xxv http://www.andrewwiddis.com

xxvi http://www.andrewwiddis.blogspot.com

xxvii http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solar_power_in_Australia

xxviii http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/election-2013/kevin-rudds-500m-boost-for-car-industry/story-fn9qr68y-1226698798673

Some further reading:

Reshoring manufacturing jobs in spotlight at Northern California summit

By John Guenther

http://www.caeconomy.org/reporting/entry/reshoring-manufacturing-jobs-in-spotlight-of-northern-california-summit

‘Half chips, half rice’ approach to reshoring

By Andrew Bounds

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/16ef404e-8b42-11e2-b1a4-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2d2togVAE

US manufacturing and the troubled promise of reshoring

By Mubin S Khan

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2013/jul/24/us-manufacturing-troubled-promise-reshoring

New Tax Protects Britain Against Cheap Chinese Imports

http://www.dudson.com/news/company-news/new-tax-protects-britian-against-cheap-chinese-imports

The new publication

The new publication