How contemporary jewellery breaks the alliance of risk and management.

Risk management

Like other media around the nation, The Age newspaper heralded the recent carbon tax as ‘Julia’s Gamble’. It’s an odd take. How could such a bureaucratic exercise as an emissions levy be viewed as a game of chance? The immense business of re-aligning flows of capital across the nation comes down to a fragile human drama—how one politician manages to hold herself together as she walks the gauntlet of media and public. Good policy isn’t quite enough. We still need to toss the coin.

We are awash with statistics of Australia’s impecunity. Complementing our astronomical greenhouse emissions are regular reports of our addiction to gambling. Last year, the gambling turnover in Australia was $153 billion. An Economist special issue had Australia as a world leader in the amount of gambling spent per capita—each Australian loses on average $1,300 a year, or $22 billion. The Australian Gaming Council is understandably optimistic, expecting a four-fold increase in TAB and on-course gambling.

It is not just the amount of gambling that we notice, but its increasing reach into daily life. Gambling odds are now seen as incisive augers of the fortunes of political parties leading up to an election—‘money doesn’t lie’. Gambling is presented as a way of supporting your favourite team. The website for the online betting business 888 Australia talks up gambling as a form of participation: ‘Instead of screaming from the MCG side lines, why not bet on the game… nothing says confidence and support like a placed bet.’ Gambling ‘products’ go beyond the final outcome to continuous odds and idiosyncrasies, such as the first goal. The ‘one day in the year’ when Australians used to ‘flutter’ has come become every second.

It is not just the amount of gambling that we notice, but its increasing reach into daily life. Gambling odds are now seen as incisive augers of the fortunes of political parties leading up to an election—‘money doesn’t lie’. Gambling is presented as a way of supporting your favourite team. The website for the online betting business 888 Australia talks up gambling as a form of participation: ‘Instead of screaming from the MCG side lines, why not bet on the game… nothing says confidence and support like a placed bet.’ Gambling ‘products’ go beyond the final outcome to continuous odds and idiosyncrasies, such as the first goal. The ‘one day in the year’ when Australians used to ‘flutter’ has come become every second.

The current flood of gambling reflects a familiar metaphor for the Australian condition. The ‘lucky country’ has been able to ride out the GFC thanks to the good fortune of its mineral deposits. Thus an exhaustively planned policy to introduce a carbon tax is viewed as a toss of the coin.

Given this, one could be forgiven for seeing gambling as a source of grand evil in Australia. But is playing with luck always a lost cause? Why go a half measure in mandatory limits for poker machines? Why not ban gambling completely?

The prospect of a world where chance is over-regulated evokes the other blight on Australian society—managerialism. Those working in universities decry the way teaching and research is reduced to quantitative accounting, leading inevitably to the bottom line. What Frank Furedi in the Times Higher Education calls ‘the formalisation of university life’ entails the removal of context and judgement from academic practices. The aim of ranking schemes like ERA is to serve a dashboard hierarchy in which the complexity of research can be reduced to a series of dials sitting on the desks of managers.

Similarly, we decry how managerialism has infected politics. ALP ‘machine men’ put public polling before ideology. The expanding ad-scapes in public transport are evidence of the public-private partnerships that seek to capitalise on common needs.

Risk and its management seem to be our Scylla and Charybdis. On the one hand we have a blatant disregard for money in compulsive gambling, and on the other an over-valuing of it in managerialism. Are they symptoms of the same cause or potential antidotes of each other?

The spirit of risk has become industrialised in clubs like sweatshops milking the unmet human need for chance. Capitalism has become hyper-efficient in gathering huge fortunes, but unable to build anything enduring with it. With Crown Casino, the Packer empire has blossomed as both a player and consumer of the lucky dollar. The bulimic alliance of capital and its purging needs to be broken.

The key is in the lock, we just need to turn it. Gambling is a natural antidote to managerialism. In its traditional context, gambling can be effective in countering the sacred quality of money. The ‘lucky dollar’ is usually taken out of circulation and used as a charm. The ‘luck economy’ reveals the fetish element of commodification. In Singapore, shops selling charms quote prices with lucky associations, such as $388. Rather than the atomised scene of pokie venues, traditional gambling is intensely social. Balinese cock fights or two-up in Melbourne lanes were scenes of vibrant local culture.

The alternative currency of contemporary jewellery

Melbourne has recently been the site of radical jewellery practice that seeks to question conventions of value, particularly in monetary form. This group sits within the marginal but globally diverse realm of contemporary jewellery.

The ‘movement’ of contemporary jewellery began in post-war Europe as a critique of preciousness. The aim was to liberate ornament from a purely monetary value. Rather than use only diamonds and gold, artists celebrated the preciousness of alternative materials, such as aluminium and plastic. While this was initially a way of giving value to labour, particularly creative innovation, recent jewellers have been more radical in questioning the basis of monetary value itself.

This occurs today in various parts of the world. At the annual festival of ornament in Munich, Schmuck, the jeweller Stefan Heuser presented a work titled ‘The Difference Between Us’. It consisted of one hundred identical cast sterling rings. The only difference between them was price, which ranged from $1 to $100 in dollar increments. Monetary value was the only element separating the rings. While most rushed to buy the cheapest rings, a few chose prices for aesthetic reasons. Would you prefer a ring costing $49 or $88?

Ethical Metalsmiths from the USA promotes jewellery production that doesn’t involve environmentally damaging mining. In their Radical Jewelry Makeover events, participants bring their unloved jewellery to be recycled into new original pieces. They receive a credit for their contribution which goes toward purchasing a new piece. Money doesn’t have to change hands, just the bracelets.

Jewellery provides a way of deconstructing money as a material substance. In a recent survey of Latin American jewellery, Argentinean Elisa Gulminelli created a small sculpture that juxtaposed a mountain of pesos from the past with a tiny coin representing their current equivalent. What’s today’s currency is tomorrow’s trash.

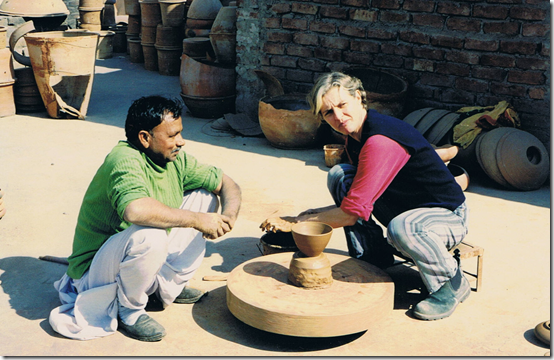

In New Zealand, Matthew Wilson has applied his Maori heritage to the fine weaving of metal. Alongside this, he has developed a striking technique of extracting the motifs of coins from their background. Out of mass manufactured articles, he has created individual works of art. There is something magical in the way he has liberated coinage from its heavy duty of exchange. His work brings into stark relief the enduring national symbols.

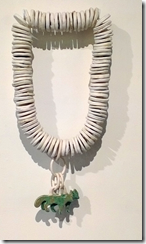

In Melbourne, a particular school of urban jewellery has evolved that seeks to make value out of nothing. This can involve collecting aged plastic from gutters, as Roseanne Bartley does in her Seeding the Cloud project, where she her Coburg neighbourhood to create an elegant necklace out of what the streets provide. Bartley is a New Zealand ex-pat who was originally taught bone-carving by a Maori in Auckland. She has specialised in using leftover materials, such as her series Homage to Qwerty that made handsome jewels out of typewriter keys and strikers. She has been particularly interested in the sociology of jewellery as a way of connecting people together, even constructing human necklaces for a performance work. Seeding the Cloud employs the jeweller’s craft to create poetic expressions of place out of its detritus.

Her colleague Caz Guiney has evoked great controversy in questioning notions of preciousness. Her City Rings project in 2003 placed gold ornament in secret locations around Melbourne CBD, such as a gold brooch on a rubbish bin. This quickly became the topic of the day for talk radio, as government funding was seen to be thrown away on trash. In an almost atavistic ‘gold fever’, prospector scaling city buildings to find Guiney’s jewels. Guiney eventually had to call her project off to prevent law suits from those injured in the process. Since then, Guiney has continued in a more modest way to plant jewellery in public urban spaces, short-circuiting the relationship between preciousness and private property.

More recently, the collective Part B has sprung up to realise jewellery ‘flash mob’ style events in the city. Last year, their exhibition titled ‘Steal This’ invited the public to come and steal works on display in a Melbourne lane. Another collective, Public Assembly, is located in the Camberwell Market and produces jewellery from curious vintage objects that visitors find in the nearby stalls. The resulting pieces can then be paid for by donation. For these collective jewellers, the worth is not in the materials themselves but the stories that people bring with them.

Of particular note is the project by Vicki Mason, Broaching Change Project, which is designed to introduce the idea of an Australian Republic into everyday life by person to person contact. She has produced three beautifully made brooches based on the wattle, oregano and rose, as currencies of communal gardening. Despite their obvious value, she distributes these for free. The only proviso is that when someone notes how attractive these are, you are obliged to give them over, as long as they agree to do the same when it comes to them. Since the project started early 2010, various hosts of these brooches have been contributing their comments about a garden-led republicanism.

Such jewellery re-connects with the origins of ornament as a form of protection. By contrast with the pearls and diamonds that find a resting place on the bodies of the status-conscious wealthy—with little resale value—the power of amulets increases through circulation. We need to put Pandora back in the box and put on the heirloom charm bracelets.

Gambling can be a source of social connection by demystifying the power of money. But this has become industrialised in our time. Far from opening our lives to chance, it furthers our atomisation. Risk or management, which is it to be? Heads or tails?

A version of this article was published in Arena Magazine, #113, 2011. It was written as part of New Work grant supported by the Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council.

The Australasian Craft Network has been established as a bridge down-under with the World Craft Council.

The Australasian Craft Network has been established as a bridge down-under with the World Craft Council.