Danius Kesminas embodies some of the wilder energies of the Australian cultural scene. The tireless Melbourne artist is very much embedded in the art world – his exhibitions in a cutting edge commercial art gallery quote from modernist art history. Yet Kesminas’ work is far from pretentious: his many projects set about attacking art’s elitism by popularising its most privileged secrets. His weapon of choice is rock music, particularly Punk. His band Histrionics perform songs about revered contemporary artists, like the Thai relational artist Rirkrit Tiravanija who transforms galleries into restaurants. The lyrics follow a familiar tune: ‘I don’t like Rirkrit, no, no / I love him, yeah /I don’t like your bean curd / Don’t mean no disrespect / I don’t like your tofu / If this dish is an art object.’

Kesminas shares a Lithuanian background with the founder of the Fluxus movement, George Maciunas. He acknowledges Fluxus in the project Vodka Sans Frontières, which traces an illegal vodka pipeline that travelled under Maciunas’ house in Vilnius. But in a different way, Kesminas’ work also seems quite at home in an egalitarian country like Australia, where the elitist authority of global visual arts has relatively little purchase.

So we might be surprised to learn that Kesminas has commissioned work from traditional Indonesian artisans. This would seem exactly like the kind of naive ‘politically correct’ art world project he would make the target of his satire. Despite its seeming worthiness, Kesminas has been able to develop an anarchic mode of collaboration which challenges our understanding of what it is to work with artisans.

At the end of 2005, Kesminas arrived in Jogjakarta for a three month Asialink residency. His only preparation for the new culture was reading a book, The Politics of Indonesia, by Damien Kingsbury. It was a dense read, filled with acronyms. Despite their inscrutability, these acronyms would later end up being an important creative resource.

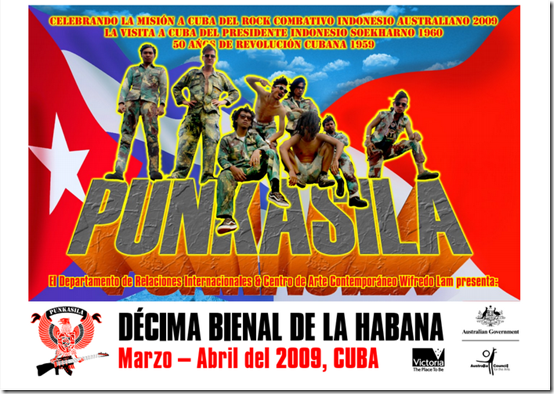

Soon after he arrived, Kesminas started hanging out at the local art school. There he found a familiar scene of young rebels playing aggressive rock music. So he decided to form a band of his own and went about recruiting musicians, with immediate success. As Kesminas didn’t speak any Indonesian, they created lyrics together that were inspired by the acronyms he had read. Fortuitously, this method corresponded with a local word game plesatan, which sends up official language. For example, the song TNI is based on the acronym that stands for Tentara Nasional Indonesia (Indonesian National Military) but which is sung as Tikyan Ning Idab-Idabi (Poor but Adorable). In a similar vein, the band adopted the title Punkasila, which is drawn from the concept pancasila, the official five ideological tenets of Indonesian nationalism.

Danius Kesminas with locals celebrating the carving of the Punkasila emblem (photograph supplied by artist)

Local involvement in Punkasila expanded rapidly. A batik artist produced the band uniform in military camouflage. A wood artisan carved elaborate machine-gun electric guitars from mahogany. Others produced t-shirts, stickers, videos, etc. Much of this was well beyond Kesminas’ control, but this was exactly as he wanted it – ‘you’re a catalyst lighting this wick.’

Like many foreign artists, Kesminas enjoyed the freedom to make art in Indonesia. He contrasted this with the situation in a country like Australia where everything has to be paid for – ‘over there it’s different. You just do things because you do them.’

Given the role of the military in Indonesian life, Kesminas was afraid their provocative repertoire would endanger his collaborators. He claimed that he ‘always had to defer to them for limits. We never did anything they didn’t want to do.’ Yet at the same time, he recognised that his role as an outsider was critical: ‘There was a nice unspoken agreement. I gave them a kind of cover, as a naïve Westerner.’ It’s hard to tell who is using who in this situation. Even though punk is an identifiably Western popular movement, Kesminas associates it more broadly with a DIY principle of cultural independence. Like the paraphernalia that was locally made for Punkasila, it represents self-sufficiency in culture and defies a reliance on imported readymade products.

For Kesminas, the most significant complaint against Punkasila came from ‘NGO do-gooder missionary types’ who thought he was showing disrespect for Indonesian culture. Kesminas would claim that he actually more respectful by following the authentically carnivalesque nature of Indonesian street culture. According to this line, what we normally associate with Indonesian traditions, such as Wayang, is just a cultural commodity sustained for Western tourists. The real life is on the street.

There’s plenty to suspect Kesminas of. ‘So he likes the fact that they don’t have to be paid! But, hey, doesn’t he end up marketing their product in his exhibitions back in Australia?’ This line of interrogation seems to be missing the point, and indeed play into the very stereotype of political correctness that Kesminas’ satirises. As far as I know, the work based on Punkasila has not sold. In the meantime, Kesminas raised money for his fellow band members to participate in the Havana Biennale, which profiled them on an international stage. Sure, it all contributes to his cultural capital, but compared to other artists who use artisans like Jeff Koons, it’s relatively high on the scale of collaboration.

Indeed, there’s something quite refreshing about Punkasila. It makes us re-consider whether work with artisans must only be in forms that they are familiar with. It adds a pinch salt to our sanctimony and a dash of chili in our philanthropy.

But in the long run, there may be problems. While an important detour from cultural conservatism, we need to admit a certain guilty pleasure in Punkasila. It shows an image of Indonesian society that reflects back our familiar ideology of Western individualism. In the spirit of good ol’ rock’n roll, we have a natural tendency to champion those individuals who defy authority. We join them in solidarity against local leaders – the patriarchs, warlords and ‘tin pot dictators’.

But who are these foot solders really fighting for in the long term? We need to think of the broader context. Countries like Indonesia face significant pressures from overseas companies to ‘open up’ for ‘development’. So why should the polygamous village elder stop you from selling your land to Monsanto? Who’s the fat old chief to say you can’t sign away royalties for your village’s traditional chant? While rock’n roll is great for breaking things down, such as a military regime, it’s not disposed to building new structures.

Thank god that Kesminas has finally let the cat out of the bag. But the mice better to get organised.