At the same time that the long-awaited NAVA National Craft Initiative report was released, the US Whitehouse hosted its first Maker Faire. It makes an interesting comparison.

With the de-funding of Craft Australia, the Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council directed the money saved to NAVA, who were charged with writing a report on the craft sector and organising a conference. The report is finally out now and looks an impressive document. It’s especially good at covering the broad spectrum of craft and design organisations. As to be expected, it argues that craft practice is diversifying and needs greater promotion. Hopefully, the document will be useful in arguing the case for continuing support for craft practice, but it should be especially useful as a springboard for discussion in the conference planned for 2015.

It’s worth at the same time listening to Barack Obama’s speech to inaugural the first Maker Faire to be hosted by the Whitehouse. With a great comedic sense of timing – ‘I’m just saying…’ — Obama lists the numerous innovations on display that demonstrate US entrepreneurship. What’s especially impressive is the easeful way he invokes the many individuals involved, as though they are all his buddies. It’s a far cry from the anonymous acronyms and corporations that normally represent technological development. The personalised account matches this form of economic development with a democratic ideology. We are all familiar with this narrative of opportunity and dream – Obama plays it to perfection.

The coincidence of these national celebrations of craft leads us to question what the metanarrative of craft in Australia is, or more broadly what kind of story is leading our creative energy. There’s little in the report about the place of craft in society, and in particular the tension with an extractivist economy that locates value below ground rather than what we can make above it. What does Australia have that matches the English sense of tradition, Italian luxury, Germany technique, Scandinavian simplicity, Indian workmanship, Chinese industry or Latin American folk culture?

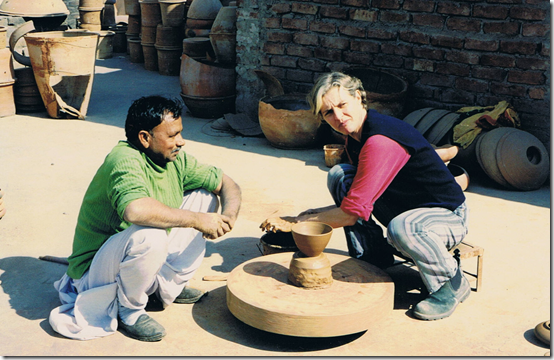

While DIY has become official ideology in the USA, it is possible for Australia to make a virtue of its capacity to work in partnership with its neighbours. Australia has the capital that enables it to take risks, offering spaces for innovation. Our neighbours like India and Indonesia have great craft capacity that is currently under-valued. We have an ability to strike a deal between capital and labour that embodies mutual respect rather than race to the bottom. This could be what distinguishes Australia.

I’d argue for Australia’s virtue as a good friend in our region – dare I say a ‘mate’. It’s our capacity to work with others that distinguishes us from other more established cultures. For all the seeming contradictions in this picture, at least it would get the argument started. What do you make of Australia?