Opening address for the Taiwan Ceramics Biennale, Yingge Ceramics Museum, 3 May 2014

I’ve come from the state of Victoria, in south-eastern Australia, where last month there was a very touching event. Two designers Ben Landau and Lucile Sciallano had been exploring the soil on a Victorian farm to prospect for a workable slip to make ceramics. The owners practiced organic farming, not only providing restaurants with their produce but also taking away the waste for their compost bins to plough back into their soil. As it turned out, the local couple were in the process of planning a wedding. Landau and Sciallano proposed to make crockery for their feast, direct from their soil, which afterwards would be smashed and left to merge back into the soil. And thus a marriage was consummated in a wonderful cycle of earth, reflecting the life cycle, of which marriage is arguably the traditional the peak of life between birth and death. It’s an inspiring example of the cradle to grave sensibility that is espoused by ethical design.

While this a touching exception to most consumption, which cannot account for its waste, there are places where the clay cycle is an everyday event. In India, potters produce small cups, or kullarhs, out of clay scooped from the river. These are dried in the sun and then half-baked on an open fire. Batches are sold to those selling spiced tea, or chai, on the street. Before filling the cup, the chai wallah taps it to dislodge the loose clay. In train stations, the cups are called pi ke puht—pi ke means ‘to drink’ and puht is the sound it makes when it hits the tracks, thrown away after use, dissolving back into the soil at the next rain.

There’s something about the linear orientation of modernity that finds this zero-sum process threatening. Melbourne designer Sian Pascale has produced chai cups that are embedded with flower and vegetable seeds. By contrast to most consumer items, their disposal is a positive act. Nonetheless, these are ironically prized as collector items and few find their true destiny on the ground.

Also from the Victorian countryside, ceramicist Sandra Bowkett has been collaborating with traditional potters in Delhi to make products using their methods and skills. Their shared concern is that mass-produced plastic items like buckets and cups will make redundant the handmade production of everyday ceramic items. But for her local market, Bowkett has resorted to high-firing the chai cups, so that they can be used multiple times.

As moderns, we are conditioned to both destroy traditions and preserve things. The German philosopher Walter Benjamin evoked the image of an angel of history, hurtling backwards to the future, witnessing the trail of destruction produced in its wake.[1] While we invested in science and technology to develop ever new modes of living, at the same time we also built museums to preserve what gets left behind. Now empires of the cloud such as Google and Facebook promise to hold memories beyond the limits of space as well as time.

As a modern movement, studio ceramics has celebrated the timeless masterpiece. In the raku technique, the vessel bears the traces of ash and salt from the kiln, frozen in time by the firing process. For an artist like Peter Voulkos, it is his highly gestured making process itself which is captured in the fired product.[2] Like the modern art of photography, studio ceramics has sought to hold back time—not so much the Cartier-Bresson encounter of lovers on the street, but the alchemical interaction of elements in the fire.

Time cannot be dammed up for ever. While, the challenge of digital technology seemed to be storing information, in the 21st century it is about channelling flows of data—the feeds, tweets, streams, instagrams, Facebook updates, chats and snapchats that burst on to our screens when we turn on our mobile devices. In what Zygmund Bauman called our ‘liquid modernity’ (Bauman 2000), we are beginning now to experience this flux in the very institutions once designed to contain it. Corporations become ever more mobile as they migrate operations for one side for the world to the other in search for bigger profit margins.

Ceramic Art captures the flux in dramatic ways. In 1995, Ai Weiwei captured on camera the act of dropping an antique Han dynasty vase. Artists like the Venice Biennale duo Fischli and Weiss are increasingly using unfired clay to depict a world that is provisional and changing. We no longer always expect that the ceramic work will be the same at the end as it was in the beginning of the exhibition. You can’t step into the same river twice.

What does ceramics as process mean for the tradition of studio work? Is it a dinosaur destined for extinction with the advent of our process-based lifestyles? How does the museum, once dedicated to conserving treasures for posterity, open its doors to the rivers of mud flowing through contemporary ceramics?

The Taiwan Ceramics Biennale provides a rare opportunity to experience the power of clay to express the cyclical nature of things. Some works do this in a thematic manner, addressing the downside of our gaze upward to economic growth. While much in media advertises the products and experience that promise happiness, it’s clear that our world is characterised by considerable loss. With development comes a decline in bio-diversity: an estimate of 10,000 species becomes extinct every year. But this is just one statistic among many that we learn every day. It takes a work like Ivette Guier Serrano’s Vestiges depicting dying birds to bring it home to us. When we confront this loss in the presence of a physical object, occupying the same space as our bodies, it connects with us more directly than an abstract statistic or flat photograph.

The destruction of cultures resulting from colonisation is an especially powerful theme. Gustavo Perez depicts ancient cities in ruins. Kukuli Velarde forges a unique Peruvian ceramics to represent repression of Indigenous cultures by Catholic Spanish colonisers. Bouke de Vries takes this to a universal scale by invoking a potential nuclear apocalypse.

These are powerful works that use the quality of fired clay to offer us a subtle form of repose from the world. But there are many artists in this show that make this melancholy part of the very medium itself. After all, clay is a quintessentially fragile medium. Its survival is testament to ongoing human care, but its destruction also bears witness to violence and decay.

In the West, the increasing concentration of manufacturing in the industrial centres of China and south-east Asia has decimated large-scale ceramic production. After financial misadventures, Wedgewood went into administration with Deloitte in 2009, which led to the transfer of production to Indonesia. The loss of this capacity is ironically the source of new work in ceramic art. Neil Brownsword has made an artistic career out of laying the tradition of English industrial ceramics to rest. Elsewhere the deserted factories have been eulogised in the haunting photography of Grzegorz Stadnik, depicting the ruins of the Książ Porcelain Factory in Walbrzych, Poland. We can even read Francesco Ardini’s remains of the banquet as an allegory of the end of aristocracy that founded the great porcelain workshops of Europe. But this mourning of the industrial is not restricted to the West. Yanze Janze’s work is about the moulds that are discarded in the industrial process. The Indonesian collective Tromarama have created exquisite installation reflecting on the destruction of Dutch heritage in Bandung. Finally, Shlomit Bauman reflects a planet that is straining its natural limits, invoking the potential disappearance of clay deposits.

We find elsewhere in the use of ceramics by artists much use of unfired clay. The 2013 work Shams (Sun) by Algerian Adel Abdessemed is a gallery wall covered entirely in a clay relief that depicts workers on a building site, hoisting sacks of materials up ladders. Its display in Qatar evokes the toiling immigrant workers who construct these new mega-cities from their labour, for which they receive around $100 a month. By the end of the installation, the clay has dried and elements have fallen to the ground. Also last year, the Swiss duo Fischli /Weiss exhibited Suddenly this Overview (1981-2006) at the Venice Biennale, including 200 unfired sculptures representing various kinds of human endeavour. By contrast to the monumentalisation of labour in the 20th century, these works reflect its evanescence, as hidden toil has replaced honourable craft. From Korea, we see the extraordinary dissolving architecture of Juree Kim in her Evanescent Scape (2011). Finally, the Argentinean Adrián Villar Rojas used unfired clay as a medium to produce a body of work about the tragic rock star Kurt Cobain, whose form cracks apart with time, even sprouting potatoes.

As an Australian, I’m particularly touched by the work of Pip McManus. Night Vessel uses the solubility of clay to evoke the evanescence of life as experienced by those who resort to taking leaky boats in order to seek asylum in countries like Australia.

It is easy to associate this breaking, cracking or dissolving of ceramics with a type of loss. But there are ways in which it can be precisely the opposite, almost a celebration. As we saw in the wedding, many social rituals express an explosion of joy in wilful collective destruction of material things. Besides the breaking of plates at Greek functions, there is the smashing of the glass at Jewish weddings, the breaking of the champagne bottle at the launch of a ship, the Russian tradition of tossing vodka glasses into the fire and so on.

Why is this the case? Isn’t it vandalism to celebrate the loss of things of utility and beauty? According to the French sociologist George Bataille, the condition of our sociality involves the production of surplus value, which provides material for sacrifice. This wilful destruction implies that the social bond is more important than mere things. In his book Accursed Share, he writes:

Light, or brilliance, manifests the intimacy of life, that which life deeply is, which is perceived by the subject as being true to itself and as the transparency of the universe… From the start, the introduction of labour into the world replaced intimacy, the depth of desire and its free outbreaks, with rational progression, where what matters is no longer the truth of the present moment, but, rather, the subsequent results of operations … It is this degradation that man has always tried to escape. In his strange myths, in his cruel rites, man is in search of a lost intimacy from the first. Religion is this long effort and this anguished quest: It is always a matter of detaching from the real order, from the poverty of things, and of restoring the divine order. (Bataille 1988, 7)

If there is indeed a hunger in us for the present moment, then many works in this exhibition seek to satisfy it. In the centrifugal moments photographed by Martin Klimas, we can celebrate the singular beauty of destruction. You could argue that, until prevented by health concerns, the act of walking over the pieces in Ai Wei Wei’s Sunflower Seeds at the Tate Modern is an act of collective defiance. But also evoking Ai Wei Wei’s wilful destruction, Rocky Lewycky makes a dramatic intervention on the mindless production of consumer items.

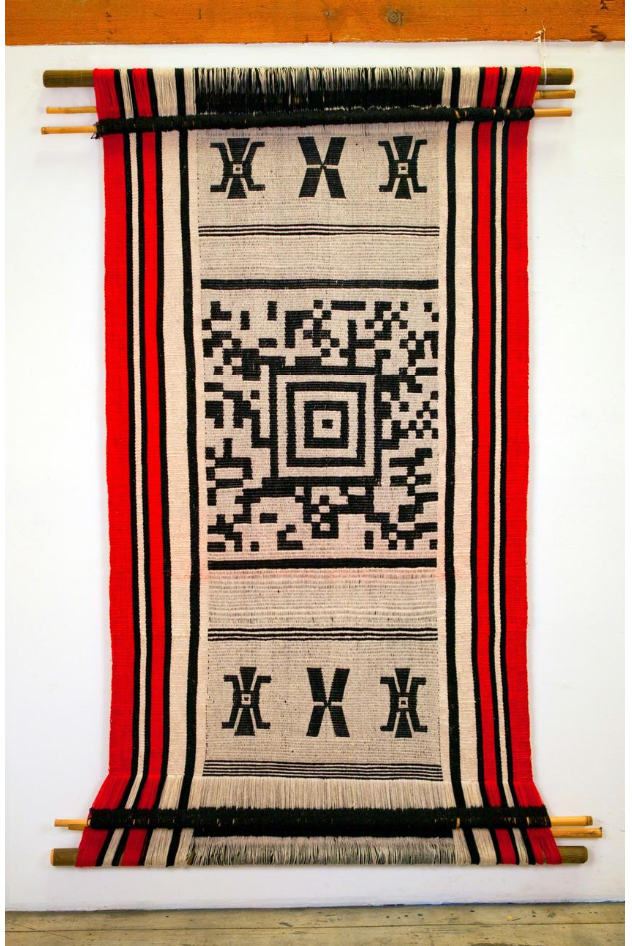

What this biennale introduces into ceramics as process is the inclusion of work whose essence is not material, but abstract. As I mentioned earlier, the drive for ceramics as process is partly coming from the changing nature of technology. Some pieces give us the chance to reflect on this. Francesco Ardini creates work between the real and the ever-expanding dimension of the screen. Twitter subjects to a heady flow of information without stop. Of the more the 300 billion tweets that have been sent so far, it is likely that around 100 million have been sent since I started talking. David Gallagher helps us materialise the abstract flows of information that forms the world of twitter.

Some use technology that augments ceramics with sound. In Nicola Boccini’s Evolution 14.0, the work is the space of potential between the ceramic panels and the voice and touch of the viewer. Pierlugi Pompei’s Whispers enable visitors to explore a world of sound in ceramics.

With the advent of 3D printing, we see the focus move from the object itself to the code that it embodies. The work of Brian Peters concerns not the individual ceramic object but its Lego-like potential as a building block for other things. For Unfold’s L’Artisan Electronique, the romantic idealisation of pottery as a direct manipulation of materials is replaced by a mediated process, in which the hand sends signals to 3D printing devices. Their Stratigraphic Manufactury extends this to a relational space allowing others to intervene in this process. By contrast with the fixed world of studio ceramics, these mediated works reflect an as yet unrealised potential.

We see in this biennale and other contemporary works an exploration of ceramics as process. The result is not a fixed object, but instead a sequence of events such as gathering, drying, firing and breaking, whose meaning is their connection with each other. This opens up powerful emotional experiences, with narratives of decline and loss. As gifts and heirlooms, things can connect us; but as subjects of avarice and greed, they can also keep us apart. Sometimes, their destruction is cause for celebration.

But where does this leave what has gone before us? It is tempting to see this new work, particularly that which employs state of the art technology, as superseding the previous focus on mute objects. It is quite significant, therefore, that the curator has selected more traditional works, particularly from southern Africa. The Zulu ceramicists including Nesta Nale and Clive Sithole continue the tradition of village ceramics that glow with burnishing. Of course, this has its own relational meaning, particularly as beer pots to be passed around. This tradition is inflected through a Western idiom by the South African Clementina van der Walt. But the objects themselves remain a testament to the survival of a culture—what the New Zealand Māori call taonga, or treasures. I’ve been particularly impressed with the work of Manos Nathan, a Māori ceramicist who, besides works of art, makes items for traditional use, such as his bowl of the burial of the placenta, Waka Taurahere Tangata, which ties the newborn to the land.

It could be argued that ceramics as process gains its energy from its contrast to what has preceded it—ceramics as production of timeless beauty. The value that is dammed up in this field has provided the stored energy which is released through this biennale today. The creative spirit of art has defined itself against the conservative discipline of craft. But this does not mean that ceramics as process has transcended its studio precursor. We can see this too as a cycle, like the rhythm of intake and exhalation in breathing. Eventually, this flow may be expended, and we seek solace again in the stillness.

This biennale offers us a chance not only to admire the combination of skill and materials that produces timeless works of beauty, but also to experience its evanescence. As Lao-Tzu says, ‘The wise man delights in water’.

Notes

[1] “This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.” (Benjamin 1970)

[2] The concept of sculpture as process involves the capacity of the final object to record its act of creation (see (Krauss 1981). However, this concept of process stops at the point of firing, when the object becomes a collectable item.

References

Bataille, Georges. 1988. The accursed share: an essay on general economy. New York: Zone Books.

Bauman, Zygmunt. 2000. Liquid Modernity. Cambridge, UK; Malden, MA: Polity Press ; Blackwell.

Benjamin, Walter. 1970. “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” In Illuminations. Vol. 1. Schocken.

Krauss, Rosalind E. 1981. Passages in Modern Sculpture. MIT Press.