Living Blue: Cultures-Based Innovations in Natural Dyeing and Sustainability Symposium | Sangam.

Tag Archives: textiles

Ruth Hadlow textile journey on 18 November

Unpacking my Library: Textile tales from West Timor

an illustrated lecture about textiles & culture in West Timor

by artist, writer & educator Dr Ruth Hadlow

The University of Melbourne

Harold White Theatre

757 Swanston St (near Gratton Street) – Rm:224 – Flr:2 (1st Floor) Enter via the external stairs next to the School of Graduate Studies or up the internal stairs at the back of the foyer. Theatre is on the right.

Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning

Monday 18 November, 6.00pm

Dr Ruth Hadlow went to West Timor, Indonesia, in 1999 to study innovations in the traditions of hand-woven textiles. She discovered an extraordinary wealth and variety of cloth, all woven on back-strap looms. In 2001 Ruth moved to Kupang, and has lived there for the last 11 years, doing research on textiles and bringing up a family with her Timorese husband Willy Kadati.

With a mixture of narrative storytelling and information Ruth will explore the beautiful textiles and fascinating culture of West Timor. The talk will be accompanied by a sale of hand-woven West Timorese textiles. (NB. cash sales only)

Gold coin donation in support of YTP Training Young Weavers Program in West Timor

Presented by World Craft Council Asia Pacific Region

Batik Dreaming in Central Java

Batik is one of the world’s idiomatic crafts. Alongside techniques such as pottery, filigree, ikat, glass-blowing and wood-carving, it is a unique language of expression which has come to define a global cultural inheritance. In a rapidly dematerialising world, as more of life is conducted in the cloud, it is increasingly important that the gifts below that time has bestowed are maintained. Without space for innovation and creative exchange, skills such as batik will cease to play an active role in what we make of our world.

Within the craft canon, batik is particularly expressive. The flow of wax through the canting lends itself to a fluid graphic form, reflecting a sinuous natural world. The history of batik is the story of its surrounding culture: originating in Java, it has been influenced by the traffic of cultures in south-east Asia, including block-printed fabrics from Gujarat, Chinese jewellery and Dutch tastes.

But there’s also a subtle mystery in batik. Like darkroom photography, it works from the negative, beginning with an inverted version of its final outcome. Unlike more direct techniques such as painting, it requires a greater understanding of the interrelation between many phases of waxing, dyeing and watching. Maybe it’s that consideration of other processes that helps it reflect an interrelation of cultures.

A recent entrant to the calendar of batik events is the Semarang International Batik Festival. Semarang is a city of about 5 million on the north coast of Central Java. Founded by an Islamic missionary in the 15th century, Semarang soon fell under Dutch control and became an important trading centre, attracting Chinese merchants. Semarang shares with the other coastal batik centre Pekalongan a vibrant pesisir style featuring bright colours and graphic forms. Semarangan style batik patterns include the tamarind plant and historic features. However, the other batik towns of Central Java, such as Yogyakarta and Solo have a higher profile. But being overlooked provides the city with a powerful motive to raise its profile, particularly as the capital of Central Java.

Kampoeng Semarang is a hybrid cultural-commercial complex that has been developed by a young local entrepreneur, Miss Wenny. Miss Wenny is a new generation business woman with an interest in civic development. Her Semarang International Batik Craft Centre has transformed what was previously a dangerous area of the city into an active commercial hub. Only a year old, Kampoeng Semarang includes batik shops, restaurant, conference facilities and workshop space.

I’d been invited last year to visit Semarang wearing my World Crafts Council Asia Pacific hat. I noticed that although there seemed to be an active if small batik sector at work, there was little space for it to develop. There was no opportunity to experiment with new designs or products. A festival seemed an important step towards fostering skill development, innovation and increased exposure. To my surprise, KS quickly agreed and set a date in early May, leaving only five months for preparation. I had to credit them their confidence, but I was a little doubtful of what they could achieve in such a short time.

It was clear that we had to quickly mobilise international support for this venture if it was to succeed. The festival had to make the right impression on the local dignitaries if it was to be ongoing. And there was great promise in its future.

For the World Crafts Council, the batik festival was an important avenue for re-activating Indonesia’s presence in the region. While there is strong south-east Asian representation from Thailand and Malaysia, Indonesian participation had declined in recent years. It has been hard to activate the national and regional crafts councils.

Realising this opportunity, the newly appointed Senior Vice-President of the WCC Asia Pacific Dr Ghada Hijjawi-Qaddumi decided to attend with a mission to recruit new representatives. Her warmth and enthusiasm helped support the event greatly, and she even contributed $1,000 towards a prize for batik art in next year’s festival. Dr Ghada was joined by the President of the WCC, Mr Wang Shan, based in Beijing. China is hosting the 50th anniversary of the WCC next year across three cities, and it is important to have Indonesia as a significant part of this celebration of world craft. There was a very neat historical resonance in the WCC presence at this event, reflecting the importance of the Arab and Chinese influences in the development of the region.

Australia is a relatively newer visitor to Indonesia, though now the relationship is particularly strong with growing ties of economy and tourism. There has been a particularly rich history of batik exchange between the two countries. This has included connections with Aboriginal communities such as Ernabella and Utopia, where the batik has been particularly suitable for the fluid nature of art making. And in textile art, the influence of Indonesian batik has been important, reflected in the touring exhibition in Contemporary Australian Batik in 1989.

Now there is scope to extend this partnership to include design. Already there are fashion designers like the Queenslanders Easton Pearson who work with Indonesian batik, but there are many other possibilities for product development. Sangam: Australia India Design Platform has been growing a network of designers and craftspersons interested to collaborate. There is many prospects in expanding this network to include Indonesia.

Here we were fortunate to receive assistance from the Australian Embassy to bring two textile masters. Tony Dyer has been successful in establishing a career in batik art, sustained by overseas collectors. Dyer had last been in Indonesia nearly 40 years ago, when he was just starting his career in batik. We were able to show his work and Tony provided a hands on engagement with participating artists, swapping techniques and discussing the finer points.

Dyer was joined by Liz Williamson, Associate Professor at College of Fine Art, University of New South Wales and a designated Living Treasure of Australian craft .Williamson teaches a unit Cultural Textiles, where students have been traveling to India in order to engage rich living traditions of embroidery and dyeing. The hope was that she would find the right kinds of people and places to bring a contingent of next generation designers to Central Java. She presented her range of Woven in Asia which gave a taste of what a craft-design partnership might entail.

There were some key international players, then, for the all-important Simbolisasi (Gunting pita) opening of the inaugural Semarang International Batik Festival. Around 9am, the dignitaries started to arrive. This included the Governor of Central Java Bibit Waluyo, whose wife heads up the Crafts Council of Central Java. He was joined by the Dr Prasetyo Aribowo, Head of Culture and Tourism, Central Java, Professsor Ahman Sya, Director General of Creative Economy and Esthy Reko Astuty, Director General of Tourism Marketing. It was clear this was an event of national significance.

It was fascinating to witness the graceful nature of a Javanese opening ceremony. As with every occasion, this included elegant young women performing traditional dances. There was a fashion parade of both men and women showing colourful if demure garments by designers Anne Avantie and Ira Priyono. I was particularly surprised to see group prizes for best batik technique—it doesn’t seem the way here to single an individual out for attention. The event was officially opened by the Governor banging the traditional drum, which he did with a trill on the side before heaving into the drum proper. More significantly, he then went to the workshop to sign his name in hot wax, so it could be dyed into a commemorative batik afterwards.

For the next three days there were stalls selling batik and craft products, which helped create a buzz. The live music was particularly good, including some languorous Keroncong, a Latin inspired Indonesian music. As word of the festival spread, high profile batik artists started to appear from the elsewhere region, showing how important such a forum might be beyond Semarang city.

On Saturday night, the reason for the timing of the festival became apparent with the Semarang Night Carnival. This was worth a trip to Semarang on its own. The costuming was inventive and exuberant. An other-worldly blend of traditional and modern music brought it to life. At the final concert, Semarang was sea of colour and movement, undulating to the rhythms of Indo-pop. Who knows what might happen if the batik festival were to form a partnership with the carnival, where it could feature the craft of making costumes.

On the final day, the organisers met with the international visitors to discuss how their event might develop. It was heartening that they able to accept the shortcomings and see this as a trial run. Much could be achieved quickly by establishing a database of batik artists and creating events like workshops where they could participate. It was clear that there wasn’t a media network that could assist organisations like Kampoeng Semarang to get word out.

Now that the first Semarang International Batik Festival is over, we can start dreaming of how it might develop. Would a prize be important, or is competition against the more collective nature of Javanese culture? Is there scope for individuals to develop pathways into batik as an art form? Would there be interest in collaborations with foreign designers?

One issue that did come up in the discussion was the depth of meaning attached to batik. Traditionally, it is a textile that gives meaning to life, with different patterns reflecting various rites of passage, such as pregnancy. I personally am interested in the labuhan ceremony, where people gather on the beach to throw their troubles in to the sea.

A challenging space has been opened up between the Semarang International Batik Festival and the Semarang Night Carnival—between batik as a product and the rituals that bring people together. There is much life in that space between.

A challenging space has been opened up between the Semarang International Batik Festival and the Semarang Night Carnival—between batik as a product and the rituals that bring people together. There is much life in that space between.

Semarang has shown it is willing and capable of holding an international batik festival. It’s up to us all now to work together and help make the next one realise this promise.

If you have any comments or suggestions for the next Semarang International Batik Festival, please leave them in the comments below.

To stay in touch with future activities of the World Crafts Council Asia Pacific, subscribe to the newsletter at www.australasiancraftnetwork.net.

Thanks to the Australian Embassy, Jakarta, for supporting the Australian contingent, as well as Liz Williamson and Tony Dyer for giving themselves to the event. Pungki Purwito and Riza Radyanto organised the initial tour through Semarang, December 2012. Thanks for Wenny Sulistiowaty and Teguh Imam Prasetyo at Kampoeng Semarang for their commitment to batik. James Bennett and Jan Nealie provided much useful advice on the history of Australian-Indonesian batik exchange. Peter Craven helped greatly with the Indonesian connections. Malcolm Smith offered a warm welcome to Yogyakarta. And special thanks to World Crafts Council colleagues Dr Ghada Hijjawi-Qaddumi and Mr Wang Shan for giving their time to this precious event.

A long and winding road through Rajasthan

Generally, I get a privileged view of what’s happening in world craft, filtered through the programing of events such as this conference and World Crafts Council extravaganzas. But it’s getting on the road and visiting villages where craft is still practiced that I tend to learn about what’s missing from these rosy views.

I had the opportunity after the conference of going to Kishangarh to teach a workshop at the new University of Central Rajasthan. I arrived late at night, embracing the warm night air after being confined in the freezing AC in First Class (there were no tickets available in Sleeper). Stumbling across the tracks, I found my host waiting patiently, who took me to my accommodation in the Heritage Hotel. Like many developments in Kishangarh, this mock Haveli is only two years old.

I found out soon after arrival that there was no WiFi or Internet in the rooms, but the staff lent me their hotel’s own dongle so I could get a connection during the night when they didn’t need it. This is a typical Indian exchange – disappointment with services followed by a generous gesture. Perhaps there would be more reliable Internet in Australian hotels, but they would charge you for it and would happily abandon you if there was a fault.

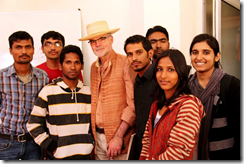

The motto of Central University of Rajasthan is ‘Education for Sustainable Development’. For our workshop, we focused on the concept of sustainability, to understand what it means to preserve the past, and when it might be better to let go. The students were mostly Rajasthani and quite idealistic about the negative impact of economic development. They seemed to embrace the discussions, offering critical perspectives on commodification. It was clear that this was a new generation of open-minded young Indians which offered much promise for all the new organisations and businesses that are starting up around the country.

After the workshop I was kindly invited by local Australian Fiona Wright and her husband to visit Thilonia, the fabled village of Barefoot College. I’d seen Bunker Roy speak about this in 2010 and found it impossibly idealistic. But seeing for myself the women from Jharkhand making circuits for solar panels, I lost any doubts about the project. It was an inspiring experience.

Wall in Thilonia where the recipients of a work subsidy are named, along with number of days and full payment. There's no escaping the truth.

Afterwards, a person who runs a new start-up for online craft sales offered to show me some villages on the way back to Jaipur. In his little jeep, we trundled down endless bumpy roads to find a village that he has been working with to supply goods for sale.

On arrival, I found myself the object of a traditional welcome. A woman came out of the house to drape a garland of flowers around my neck and anoint my forehead with a tilak red thumbprint. I do confess to a romantic notion about traditional welcome ceremonies, so was quite overcome to be greeted like this.

Residents from the village of Kashod in Rajasthan prepare something in recognition of Sangam Project.

During the long freezing drive back to Jaipur, I worked through the experience. What to do with such great expectations? Is the one-off presence of an outsider like myself sufficient in itself as an unusual event to give honour to the local embroiderers? How can a product carry values that are part of village life? There was many questions floating around, but one definite conclusion settled in my mind. I discarded any notion that Rajasthan was saturated with craft NGOs. The region has a potent combination of need, and capacity, but the challenges should not be underestimated. I do dip my lid at those who make a fist of it.

The ‘Floating Forest’ comes to Ararat

Douglas Fuchs ‘Floating Forest’ 17 February – 1 April 2012

Ararat Regional Gallery are reconstructing an exhibition that played a key role in the development of fibre art in Australia.

Douglas Fuchs (1947-86) was an American basket maker who came to Australia on a Craft Council of Australia Fellowship in 1981-82. He arrived in Adelaide in July 1981 and set up a studio at The Jam Factory, Adelaide, where he began work on his ambitious ‘Floating Forest’. Douglas exhibited three versions of ‘Floating Forest’: at the Adelaide Festival Centre Gallery from 27 November to 24 December 1981, the Meat Market Craft Centre, Melbourne from 26 January to 28 February 1982 and the Crafts Councils Centre Gallery, Sydney from 1 to 23 May 1982.

‘Floating Forest’ is widely cited as a landmark in the development of a contemporary approach to basketry in Australia (see link and brochure).

ARARAT BASKETFEST 2012 SYMPOSIUM

Ararat Performing Arts Centre, Saturday 31 March 2012, 9.30am to 4pm

Hear from key influences and experts in the fibre art field and be inspired by artists whose contemporary practices are informed by basketry techniques and traditions. The symposium supports Ararat Regional Art Gallery’s 30th anniversary exhibition of Douglas Fuchs’ influential basketry-based installation, ‘Floating Forest’, presented from 17 February to 1 April 2012, in partnership with the Powerhouse Museum , Sydney.

Key speakers include:

- Christina Sumner, Principal Curator Design and Society at the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney;

- Leading contemporary basketmaker, Virginia Kaiser;

- Antoinette Smith, Senior Curator, Indigenous Cultures of Southeastern Australia at Museum Victoria.

- Five indigenous and non-indigenous fibre artists speak about the role of tradition and technique in the creation of contemporary woven forms: Marilyne Nicholls, Bronwyn Razem, Adrienne Kneebone, Maree Brown and Lucy Irvine.

The journey begins

Sangam – the Australia India Design Platform was launched in Melbourne on 21 July.

During the day, RMIT Industrial Design hosted the Ethical Design Laboratory’s workshop into ethical labelling. Experts from around Australia met to develop a set of standards for creative collaborations. Representatives from law and design, alongside leading practitioners, considered best practice for labelling of transnational cultural products. These protocols contribute to the development of a Code of Practice for Creative Collaborations, supported by UNESCO. The results from Melbourne will be published on the website for discussion next month and then presented in Delhi at the mirror event on 21-22 October this year.

In the evening, a panel considered what it means for an Australian designer to work in India today. The coordinator Kevin Murray opened the session with a reflection on the strength of Australian designers, coming from country whose experience of reconciliation grants a sensitivity to cultural difference. This included included video messages from four designers in India. The panel was led by Moe Chiba, the section head of culture for UNESCO New Delhi, who highlighted the role of designers in sustaining India’s cultural heritage, particularly in the crafts. Local textile designer Sara Thorn defied received wisdom about authenticity and argued for the virtue of artisans working with machines in India. Architect Chris Godsell reflected on his experience in building sports stadiums for the Delhi Commonwealth Games in 2010. While providing a cautionary tale about potential pitfalls, he spoke positively about the energy and capacity of Indian partners. Finally, Soumitri Varadarajan talked about the impact that design can have in India, focusing on the issue of maternal health. Afterwards, the panel was hosted at a network dinner at the City of Melbourne, including leading figures from the Indian community and government. (A recording of the forum is available here).

Overall, the evening generated a positive reflection on the opportunities for Australian designers working in India. But at the same time, there were some important questions posed that will remain challenges for the project:

From the Australian perspective, India has much to offer in terms of rich decorative traditions and expanding market. But what then from an Indian perspective might Australia have to offer in exchange? The answer for this question will unfold at the mirror forum in Delhi later this year.

In terms of developing standards for collaboration, there is much interest in focusing previous discussions towards a set of principles that can build confidence in product development partnerships between designers and craftspersons. The next challenge is to link those standards to the market, so that they can have direct economic benefits for those involved. This a matter for future workshops that will explore models of consumer engagement, particularly with social networks.

The journey began with a buoyant march, but steep mountains loom ahead. To follow, go to www.sangamproject.net and subscribe to email updates.

Liz Williamson–a dark garland

Williamson’s work is represented in most major public collections in Australia including the National Gallery of Australia, the National Gallery of Victoria and the Powerhouse Museum. In 2008, following more than two decades of dedicated teaching at universities in Melbourne, Canberra and Sydney, Williamson was appointed as Head of the School of Design Studies at the College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales, Sydney.

For Liz, the principle form of her creative endeavour is the scarf. For Welcome Signs, she has in effect closed the scarf into a loop, creating an object that serves as jewellery, wrapped around the body.

Liz Williamson, Pendent Loop Series, 2009, photo Ian Hobbes, handwoven cotton and leather lacing, 150 x 2cm

Statement

Strands of memory, cloth and the body are interlaced throughout Liz Williamson’s practice as she explores the connections between clothing and the body experimenting with different weave structures while exploring visual and conceptual territory.

Williamson’s recent textiles play on ideas of shelter and memory as notions of containment and bodily protection, ideas presented in woven and draped shaped textiles that evoke connections with enclosing, carrying and storage while creating a place for hiding, seclusion and security.

Her Loop series are neckpieces, a hybrid between a wrap and jewellery. They play on ideas of shelter and memory on a number of levels, as their circular shapes draping the body with the contained shape inviting enquiry, a desire to know what is contained within.

Kala Raksha: Three initiatives for the artisan designer

There is an old, ongoing, and passionate debate about the difference between art and craft. This debate will probably never find consensus, but it makes us ponder and observe. Years ago, three very successful traditional artisans of Kutch gave their opinions: Ismailbhai said, “The difference is imagination and skill.” “Art is what you do the first time; after that, it is craftsmanship,” Ali Mohammed Isha elaborated. And Lachhuben added, “Everyone can do craft, but not all can do art.”

Art requires concept, imagination, thought. All craft is not art. If the artisan is simply executing patterns or rote copying, it is not art. The head and the heart are as essential as the hands.

The debate matters because it has critical implications for not just the survival but the flourishing of traditional artisans. The economic standards by which art and craft are valued are night and day apart. More than that, cultural hierarchies play out in the terms used. Craft connotes charming diminutive workers, while Art commands respect.

In art, the individual conceives an idea and executes it in his or her medium. It is an activity of self expression. Traditional arts or crafts were usually more functional. A product was created as a communication between maker and user. But as in art, the artisan both conceived the product and created it.

When the relationships between maker and user broke down, design emerged as a separate entity. In craft, it is usually called design intervention, and it indicates a separation between concept and execution. In the process, the concept retains its value, while the execution becomes labour.

In order to reverse the trend, Kala Raksha started Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya, the first design school for traditional artisans. Here, artisans learn design in order to be able to create more effectively for new, distant markets. The unique concepts of each artisan designer are valued, consciousness and confidence increase, and the art aspect of craft reemerges. Artisan Design emphasies the aspect of the artisan’s thought.

Now, Kala Raksha has added a logo to this concept, in order to create visibility and value for the individual’s creative effort. Artisan Design also creates value for the integrated spirit of tradition. This is the symbol of integration of concept and execution, and of raising status of the artisan. It is a new fair trade idea—fair trade for the creative spirit. Artisan Design certifies that a product is an artisan’s own creative innovation. It celebrates the individual’s heart, mind and hand.

The second initiative is e-portfolios of the Artisan Designers who have graduated from Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya. Each graduate has invested a year of hard work and incredible creativity, to embark on a unique artistic path. Through the e-portfolios, Kala Raksha will facilitate contact to world markets for each of these artists. The contemporary market has a critical role to play in recognizing and honouring the spirit of the creator. With information technology, emerging artisan designers can be discovered by people who can value their work. The portfolios will be maintained on a new website www.kalaraksha-vidhyalaya.org to be launched in January 2011.

The third initiative is live in time for the holiday season. It is a collaboration with Equal Craft, a socially conscious marketplace that provides world citizens with excellent world art, and artisans with true global market value and recognition. www.equalcraft.com

Combining age old tradition and the latest technology, Kala Raksha and Equal Craft are breaking social barriers. E-commerce makes it possible for rural artisans to directly connect with long distance markets. The fact that one can ask what is the difference between a quilter in Vermont selling her quilts on Etsy.com and Lachhuben Rabari selling her embroidered bags on Equalcraft.com says it all. There is no difference. The venture is leveling the playing field. The difference is that now Lachhuben can sell her embroidered bags directly to anyone in the world—and she can get direct feedback from her customers!

Equal Craft’s contemporary technology makes it possible to sell the story– the cultural and personal context that creates value –along with the product. You can follow what else Lachhuben has made. And you can ask this Rabari woman what she thought about when she created it—and get her response.

In the way that Kala Raksha Vidhyalaya offers design education to artisans with no formal education, Equalcraft.com makes social networking possible for artisan designers who may not read and write.

Yu-Fang Chi – every body has a silver lining

Yu-Fang Chi is a Taiwanese jeweller who studied metalsmithing at the Tainan National University of The Arts. She has been represented in a number of international exhibitions, including Schmuck and Talente, Korea and Japan. She is currently a lecturer in the Department of Art and Design, National Hsinchu University of Education.

Her series ‘Laced with Lace’ involves delicate silverwork that forms organic like patterns that drape over parts of the body. Chi’s work explores the space between the body and jewellery by creating work that does not obviously attach to the body as a foreign object. Her work follows the natural contours of the body as though it patterns the skin itself.

Chi’s work reflects an experimentation with form and content, applying a technique associated with needlework to metalsmithing. The result has the kind of easeful grace that we might associated with the floral garland. But its ephemerality is also a challenge. Like the traditional garland, does the fragility of this lace work limit its durability?

Chi reflects on the work in her own words:

In contrast to classical lace, objects in the “Laced with Lace” series do not have dyed or inlaid borders surrounding a central body of work. Rather these pieces are a natural extension of closeness, radiating outwards from spaces and holes at the corners and seams, following the joints and hugging the body. Through this light and fine “layer” the physical form is part of an intriguing mixture – actively “wearing” and passively being “embraced.” Without a central motif, the objects are partial forms that can be used to reflect on the past, similar to the interrelationship of the skin and the organs, alluding to the certain area of the body. – Shoulders? Wrists? Chest? Posterior? The light, mobile nature of the lace skin evolves from being merely a display, into something that is glimmering and alluring. Viewers focus on and are soon lost in the complex and difficult to understand lattice work, with no single thing on which to focus or reflect. The soaring, extending pattern causes one’s line of vision to move rapidly. Within this flattened visual experience, patterns, totems and messages are removed for a more visually stunning effect without feeling or name.

Yu-Fang Chi is one of the participating artists in the Welcome Signs exhibition

Yayasan Tafean Pah – supporting weavers in West Timor by Ibu Yovita Meta and Ruth Hadlow

News of a valuable new initiative from West Timor that deserves our support:

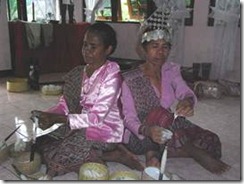

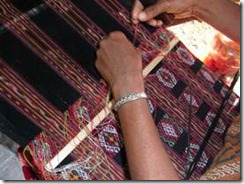

The weaving traditions in West Timor are very diverse and very beautiful, consisting of hand-made cloth woven on back-strap looms, sometimes still using handspun thread and natural plant dyes. The textiles are woven by village women amongst other activities such as growing crops, caring for livestock, social, domestic and family duties. Weaving skills are passed down from one generation to the next, with most women learning from their mothers, aunties or grandmothers. Traditional hand-woven textiles are still used as garments by many West Timorese for formal and ceremonial occasions, and textiles are still required as tribute for funerals, as part of the bride-wealth exchange in marriage agreements, and for other adat (traditional customary law) ceremonies. Despite this, the weaving traditions are fragile and vulnerable to changes in contemporary life, as the younger generations move away from villages, or become less interested in traditional textiles and the time-consuming techniques of hand-weaving.

The weaving traditions in West Timor are very diverse and very beautiful, consisting of hand-made cloth woven on back-strap looms, sometimes still using handspun thread and natural plant dyes. The textiles are woven by village women amongst other activities such as growing crops, caring for livestock, social, domestic and family duties. Weaving skills are passed down from one generation to the next, with most women learning from their mothers, aunties or grandmothers. Traditional hand-woven textiles are still used as garments by many West Timorese for formal and ceremonial occasions, and textiles are still required as tribute for funerals, as part of the bride-wealth exchange in marriage agreements, and for other adat (traditional customary law) ceremonies. Despite this, the weaving traditions are fragile and vulnerable to changes in contemporary life, as the younger generations move away from villages, or become less interested in traditional textiles and the time-consuming techniques of hand-weaving.

Background & Context

West Timor is the western half of the island of Timor, which was colonized and divided by the Dutch and Portugese during the colonial period. West Timor became part of the Republic of Indonesia when it was formed in 1945 as a reaction to Dutch colonial rule. Within Indonesia, the eastern islands (West Timor, Sumba, Flores, Alor, Rote and Savu) are the poorest part of this developing country. The islands of East Nusa Tenggara, or NTT as it is called locally, are much drier and less fertile than those of western Indonesia, and very similar to northern Australia in their climate, geology and vegetation. The island of Timor is predominantly limestone, and does not have the rich volcanic soils of Bali or Java. It has a very long dry season, from April to late November, and is hot and extremely dry for most of the year. The latter part of the dry season is traditionally known as musim kelaparan, or the starvation season, as the only foods available for most villagers are the corn and cassava they have stored from the end of the harvest period. Life for most villagers is very tough and means of generating income are very limited. Many village children do not go beyond a primary school education as their families do not have the resources to support further study. Since the late 1990’s life has been increasingly difficult for the West Timorese, due to a series of factors such as the Indonesian Monetary Crisis in 1997, a rise in the cost of living of more than 500 per cent over the past 10 years, and the withdrawal of aid projects and organisations in the wake of East Timor’s independence in 1999. There is a general lack of knowledge about West Timor caused in part by the attention to East Timor in the news media, and this often makes it difficult for organisations to get external funding or support for their activities.

West Timor is the western half of the island of Timor, which was colonized and divided by the Dutch and Portugese during the colonial period. West Timor became part of the Republic of Indonesia when it was formed in 1945 as a reaction to Dutch colonial rule. Within Indonesia, the eastern islands (West Timor, Sumba, Flores, Alor, Rote and Savu) are the poorest part of this developing country. The islands of East Nusa Tenggara, or NTT as it is called locally, are much drier and less fertile than those of western Indonesia, and very similar to northern Australia in their climate, geology and vegetation. The island of Timor is predominantly limestone, and does not have the rich volcanic soils of Bali or Java. It has a very long dry season, from April to late November, and is hot and extremely dry for most of the year. The latter part of the dry season is traditionally known as musim kelaparan, or the starvation season, as the only foods available for most villagers are the corn and cassava they have stored from the end of the harvest period. Life for most villagers is very tough and means of generating income are very limited. Many village children do not go beyond a primary school education as their families do not have the resources to support further study. Since the late 1990’s life has been increasingly difficult for the West Timorese, due to a series of factors such as the Indonesian Monetary Crisis in 1997, a rise in the cost of living of more than 500 per cent over the past 10 years, and the withdrawal of aid projects and organisations in the wake of East Timor’s independence in 1999. There is a general lack of knowledge about West Timor caused in part by the attention to East Timor in the news media, and this often makes it difficult for organisations to get external funding or support for their activities.

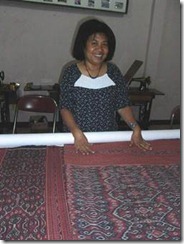

Yayasan Tafean Pah

Ibu Yovita Meta began the foundation Yayasan Tafean Pah in 1989, working with a small group of weavers from the dry and mountainous Biboki region of northern West Timor. YTP has grown substantially over the past 20 years; it now has a base in the northern town of Kefamenanu and 14 weaving cooperatives with a total of 700 members, spread over the Biboki, Insana and Miomafo regions of TTU (North Central Timor). Yayasan Tafean Pah supports the weaving cooperatives by providing access to thread and dyes, and training in weaving, dyeing and design skills. The foundation also provides cooperative management and basic accountancy training, and very importantly, provides an outlet and market for the beautiful hand-woven textiles which the weavers produce.In 2003, Ibu Yovita won the prestigious Prince Claus Award for Culture and Development (awarded by the Netherlands government) for the work she has done with Yayasan Tafean Pah. The award was used to develop the Rumah Seni Tafean Pah in Kefamenanu, a cultural centre which includes the YTP office, a multi-functional work space, and a gallery/shop outlet for the textiles and associated products made by the weavers. In 2007, Yayasan Tafean Pah received a grant from the Dutch Embassy in Jakarta specifically for the purpose of creating a collection of traditional hand-woven Biboki textiles. This collection is intended as a permanent resource for the community, ensuring that examples of the techniques, motifs, designs and textile forms unique to Biboki hand-woven textiles are held in West Timor, rather than only in the collections of distant or foreign museums. The textiles which make up the collection were commissioned directly from weavers in the YTP cooperatives, supporting them financially and increasing their sense of pride in their work.

Textiles produced by the weaving cooperatives reflect the traditions which have existed for countless generations in these regions. Some of the weavers specialise in textiles made with hand-spun thread and dyed with traditional natural dyes, such as the rich reddish-brown Morinda Citrifolia, the deep blues of Indigofera Tinctora, and blacks from iron-rich mud. Other weavers use machine-spun thread to create lighter-weight textiles which can be made up into smaller items such as bags and clothing. YTP sells the textiles through its base of the Biboki Arts Centre in Kefamenanu, and through trade fairs and exhibitions in Jakarta and Singapore. With the support of the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory there have also been several exhibitions of Biboki textiles from Yayasan Tafean Pah in Darwin.

The aims of Yayasan Tafean Pah are to ensure that traditional weaving and dyeing skills are sustained, and to support village women to develop economically through their weaving skills. In a culture such as that of West Timor, a woman’s status and standing within a village community increases significantly when her weaving contributes to the family’s economy. One of the YTP cooperatives is comprised predominantly of widows, and most of these women have put their children through senior high school and university on income derived from their weaving activity. Due to the success of its existing cooperatives, YTP is continuously requested to take on new groups, some of which have little prior weaving or dyeing knowledge. Although this is a huge burden on the organisation, it also indicates the potential for a remarkable revival and continuation of skills and traditions.

Friends of Yayasan Tafean Pah

Yayasan Tafean Pah has no continuous funding and relies on sales of textiles to support its ongoing activities. Any new initiatives require external funding as the foundation survives on a day to day basis due to the unpredictable nature of selling textiles. Because of the difficulties of this situation we have decided to begin a support project called Friends of Yayasan Tafean Pah. Through an informal network of email lists we will regularly send out information about specific projects and activities which YTP wishes to seek funding for. A data base has been set up to record information about all donations and ensure transparency. Friends of Yayasan Tafean Pah has been created by Ibu Yovita Meta and Ruth Hadlow with the intention of helping YTP to source funding through Australian textile networks and other interested parties. Ruth Hadlow is an Australian artist who has been resident in West Timor since 2001. From 2005-2009, Ruth and her Timorese husband Willy Daos Kadati ran Babes in Timor/Mepu Mfe Fafi, a small aid project dedicated to supporting the West Timorese community through donations of piglets from Australian sponsors. Ruth Hadlow and Willy Daos Kadati run textile and cultural tours to West Timor and other parts of eastern Indonesia, and have had a close relationship with Yayasan Tafean Pah for a number of years.

Yayasan Tafean Pah has no continuous funding and relies on sales of textiles to support its ongoing activities. Any new initiatives require external funding as the foundation survives on a day to day basis due to the unpredictable nature of selling textiles. Because of the difficulties of this situation we have decided to begin a support project called Friends of Yayasan Tafean Pah. Through an informal network of email lists we will regularly send out information about specific projects and activities which YTP wishes to seek funding for. A data base has been set up to record information about all donations and ensure transparency. Friends of Yayasan Tafean Pah has been created by Ibu Yovita Meta and Ruth Hadlow with the intention of helping YTP to source funding through Australian textile networks and other interested parties. Ruth Hadlow is an Australian artist who has been resident in West Timor since 2001. From 2005-2009, Ruth and her Timorese husband Willy Daos Kadati ran Babes in Timor/Mepu Mfe Fafi, a small aid project dedicated to supporting the West Timorese community through donations of piglets from Australian sponsors. Ruth Hadlow and Willy Daos Kadati run textile and cultural tours to West Timor and other parts of eastern Indonesia, and have had a close relationship with Yayasan Tafean Pah for a number of years.

If you would like to become a member of Friends of Yayasan Tafean Pah, you can contact us directly, or simply continue to receive our emails and respond as you wish to the various projects. If you have friends or family whom you think may be interested, please pass this information on to them. If you do not wish to receive emails from Friends of Yayasan Tafean Pah, please let us know and we will take your address out of the email list.

YTP project: Training Young Weavers

Yayasan Tafean Pah plans to begin a training program in the latter part of 2010, with the aim of training young women in weaving skills. There are 4 main weaving techniques used in the TTU region of West Timor: futus (warp ikat), sotis (float or pickup warp), buna and pa’uf (discontinuous supplementary weft techniques). Each of the techniques is slow and time-consuming, requiring patience and attention to detail. The majority of weavers in West Timor are older women, a matter for some concern as the weaving traditions could disappear within a couple of generations if younger women do not take up weaving. Due to the success of the existing YTP weaving cooperatives, it has become visible to the broader West Timorese community that woven textiles can provide a useful source of income. This provides a good incentive for encouraging young women to learn weaving skills as a realistic alternative to other types of income-generating work which require them to leave their villages.

Yayasan Tafean Pah plans to begin a training program in the latter part of 2010, with the aim of training young women in weaving skills. There are 4 main weaving techniques used in the TTU region of West Timor: futus (warp ikat), sotis (float or pickup warp), buna and pa’uf (discontinuous supplementary weft techniques). Each of the techniques is slow and time-consuming, requiring patience and attention to detail. The majority of weavers in West Timor are older women, a matter for some concern as the weaving traditions could disappear within a couple of generations if younger women do not take up weaving. Due to the success of the existing YTP weaving cooperatives, it has become visible to the broader West Timorese community that woven textiles can provide a useful source of income. This provides a good incentive for encouraging young women to learn weaving skills as a realistic alternative to other types of income-generating work which require them to leave their villages.

Yayasan Tafean Pah intends to start the training program with groups of 10—15 young women who will be paired with experienced weavers, either in their village setting, or at the YTP Centre in Kefamenanu. The young women will begin by learning basic weaving skills, and also, if they choose, they can learn to hand-spin cotton with a drop spindle (a difficult process if you didn’t start at age 5, as some of you know!). If the young women already have some basic weaving skills, they will be trained in more complex techniques such as buna, pa’uf or sotis to increase their skill base.

The training will take the form of 5-day intensive programs, after which time the young weavers will be encouraged to continue their work independently, and the results will be assessed by YTP once the woven textiles are finished. If they require or request further training, they can undergo a second stage of training to increase their weaving skills, or begin producing textiles under the supervision of a YTP weaving cooperative. In the long term it is hoped that the young weavers might start new weaving cooperatives or join existing ones, as a means of developing and marketing their work.

In order to run the training program, funding is needed to cover the costs of transport, food, and wages for the weaving teachers, who will give up their own weaving time to train the young women. A wage also helps to acknowledge the skills and experience of the older weavers, encouraging the community to value and respect the women’s textile skills and perceive these as an important source of income. YTP is hoping to take on between 60-100 young women in the training program at the first stage, making this quite a large and ambitious project which is intended to have a major effect on the survival of the weaving traditions in the TTU region of West Timor.

If you are interested in supporting Yayasan Tafean Pah in this program of training young weavers, please use the form on the following page to make a donation.

We would like to thank you for your interest in the activities of Yayasan Tafean Pah. If you visit West Timor and can come as far as Kefamenanu, we would love to meet you and introduce you to some of the weavers you have generously supported.

Many thanks and best wishes,

Ibu Yovita Meta & Ruth Hadlow

Kefamenanu, West Timor

To contribute to this valuable project, please contact Ruth Hadlow at friendsofytp@yahoo.com