Christine Nicholls celebrates an exhibition that brings people of craft and trades to work together.

image

‘Trades’, an innovative project conceived and sponsored by Craftsouth, Australia’s premier contemporary craft and design association, was that organization’s big ticket offering for 2008. In some respects Craftsouth operates along the lines of the artists’ and artisans’ guilds of yesteryear, offering a range of services to its membership, including the provision of professional accreditation and artist insurance. Craftsouth also plays an important advocacy role for its members. This includes mounting at least one major exhibition of members’ artwork, annually.

The Trades project was conceived towards the end of 2006 and unfolded over an extended period of time. This process-driven venture culminated in a splendid, well-received exhibition of the same name at Adelaide’s prestigious JamFactory late in 2008.

Eight practising visual artists working across a range of different disciplines were selected to work cooperatively with eight qualified tradespersons. Each artist was paired or ‘matched’ with a tradesperson. This pairing was not arbitrary but based on participating parties’ professional and creative aspirations. Each participating artist elected to collaborate with someone with a specific trade and skill set, for the purpose of skills exchange. Hence the relationships were underpinned by mutual respect and recognition of the professionalism of the contributing parties. The idea was to give the participating artists the freedom and opportunity to explore, as Craftsouth’s Niki Vouis has written, “specific skills and industry knowledge…not normally available to them in their day to day work practices” and also to provide “the tradespeople [with] the opportunity to experience…artists’ working methods, while at the same time demonstrating their own expertise and creativity”.

While the project was by no means narrowly ‘product’ or outcome-orientated, there is absolutely no doubt that several of these creative fusions produced marvellous results. This became evident in the 2008 Trades exhibition. One reason leading to this success was the fact that the individual ‘track records’ of both participating artists and tradespersons were carefully scrutinized prior to the commencement of the Trades project. Commitment from each party was sought and obtained. Whilst in progress the project was also monitored and quite closely documented.

image

|

image

|

Collaboration between furniture maker Adrian Potter and tattooist Amy Duncan

A number of extremely successful, albeit left-of-field, collaborations took place. One such partnership occurred between Adrian Potter, a qualified engineer who has worked as a professional furniture designer and maker for more than a decade, and Amy Duncan, a tattooist. The collaborative work made by this artistic ‘odd couple’ and exhibited in the 2008 exhibition drew widespread admiration.

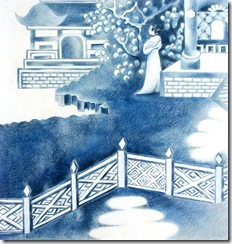

Potter drew upon his woodworking skills in his expert carving of two beautiful hollow conch shells from Huon Pine, a very large, relatively soft-wooded tree native to Australia’s Tasmania. Part of its aura derives from the fact that it is believed to be the longest-living species of tree in Australasia: it has been ascertained that in the Tasmanian rainforests there are Huon Pines in excess of 1,000 years of age. Huon Pine wood is also renowned, in Australia and beyond, for its aesthetic qualities.

Having incorporated a number of ideas inspired by Amy Duncan’s craft into his carvings, Potter passed on the larger of the two carved objects to Duncan, who subsequently designed and applied the remainder of the surface decoration. This involved the youthful tattooist working with her customary tools of trade – drawing inks, gouache infills and inlays – to decorate the conch shell carved by Adrian Potter. Duncan’s ability to execute designs and drawings on to three dimensional, curved body surfaces ‘translated’ very well to this new medium.

The artworks created by Duncan and Potter working together on this project exceed anything that either party could have created solo, as Adrian Potter freely acknowledges: “I’ve always thought that ‘collaboration’ is a fancy name for teamwork – I’ve got the skills, you’ve got the skills. We [were] working together to come up with something that you can’t do individually”.

The creative synergy forged by this pair of artists – one of whom mostly works in the relatively mainstream activity of furniture making, while the other is habitually employed in the more socially marginal pursuit of tattooing – opened up a genuinely ‘transitional space’ for both parties. In a sense, the compelling carved and decorated objects co-created by Duncan and Potter and displayed in the Trades exhibition bore the artistic ‘signatures’ of both – while at the same time giving rise to a third, unique artistic inscription that could not be said to belong exclusively to either party. A major reason for favourable critical attention enjoyed by the Potter and Duncan’s co-created artworks in the Trades exhibition was their subtlety and their integrity as artworks – their ‘seamless’ quality. With respect to their Spring Blossom Tattoo, for instance, it was not at all apparent that two persons from entirely different disciplines and backgrounds had had a hand in the work’s creation.

[See Adrian Potter’s comment below about the nature of the collaboration]

image

Collaboration between glass artist Gabriella Bisetto and scientific lamp worker Monte Clements

Another extremely productive working relationship was forged between Monte Clements, a scientific lamp worker, and Gabriella Bisetto, an established glass artist. Clements has worked in his highly specialized field for three decades, and runs a thriving Adelaide-based business. Unfortunately, to some extent his is an endangered, if not dying art. As the Trades catalogue states, scientific lamp workers “…blow Pyrex glass to produce precision instruments for various industrial sectors, from scientific laboratories to wineries. This is an extremely rare trade in Australia, with only one current apprentice nationwide”.

Glass blower Gabriella Bisetto deliberately chose Clements as her mentor because she had for some time nurtured an aspiration to learn scientific lamp work. Part way through the project Bisetto observed that:

I’d wanted to do scientific lamp work for a long time but I wasn’t sure what the material could offer or what was available in pre-fabricated glass. And while I might blow glass for several hours a week and successfully produce several objects in that week, in lamp working I can work for hours and only produce one thing, and then it breaks. And that’s because I don’t know how to do it. I haven’t been doing it for thirty years. But working with my mentor, it’s made me want to show him that I really appreciate the time he puts in, but also to feel confident that I will get to my end result over a period of time.

And indeed, working together they did eventually arrive at that desired “end result”. The co-created Bisetto and Clements artworks in Trades are stunning. For example, their compelling work entitled Anatomy Study # 1-3 and Growth – Cluster cells # 1-3, is elegant, refined and beautifully made. The Bisetto/Clements glass works displayed in the Trades exhibition were not mere curiosities but ethereal, poetic artworks in their own right.

Under Clements’ tutelage, Bisetto worked on creating miniature glass bacteria, tiny glass moulds and fragile cluster cells, and small, delicate intestines and glass lungs. “Conceptually it allowed me to move in a different direction,” says Bisetto, “on a scale and with outcomes I couldn’t achieve with hot glass. I’m making tiny work now!” Prior to embarking on the Trades project, Bisetto was already well regarded in Australia as a ‘fine art’ glassmaker, and the working relationship with Clements seems to have enabled her to take her work to a new level. Open-ended dialogue, the sharing of ideas, mutual respect and the acceptance of the occasional wrong-turn or even mistake seem to hold the key to this successful artistic partnership.

Bisetto and Clements’s successful partnership, involving the meeting place between science and art, reflects and confirms the findings of Melbourne-based Charles Green in his canonical study of collaborative practice in contemporary art. In his monograph entitled The Third Hand, (2001) Green, who over the years has collaborated extensively with his artist wife Lyndell Green, theorizes post-1960s artistic collaboration and teamwork as akin to the development of a “third hand”. This, Green posits, is tantamount to the emergence of a new, single, transcendent artistic persona that virtually obliterates the separate artistic identities or the previous artistic ‘signatures’ of individual team members. Clearly Green’s concept of “the third hand” also has implications for other participants in the Trades project, as well. Green’s notion also mirrors broader contemporary social understandings with respect to the changing nature of artistic authorship.

image

Collaboration between sculptor David Archer and plumber Rod Archer

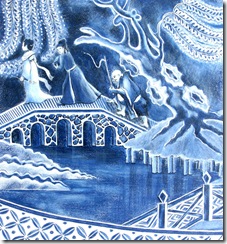

Brothers Rod Archer (a plumber) and David Archer (a sculptor) opted to work together, coming up with what was incontestably the hit of the Trades exhibition – at least with respect to mass audience appreciation. The Archer Bros’ work, entitled Pearls Before Swine, is a water powered mechanical pig fashioned from polystyrene, metal, plastic, and recycled bicycle parts. Pearls Before Swine wouldn’t have seemed out of place in the Penny Arcades of earlier eras. On the Trades exhibition’s opening night the crowd gathering around this exhibit made it difficult for many people to get close enough to view this wondrous mechanical pig. Some pig!

The pig swallows large pearls that enter its mouth in a continual loop. The plumber brother cleverly created a revolving internal trajectory powered by water energy. In turn, the pearls that the pig is constantly consuming are ‘excreted’ or converted into a continual succession of big, joined sausages. A string of enormous sausage-excreta continuously pop out of the pig’s rear end. No doubt this repetitive cycle to some extent alludes to some of the less pleasant aspects of plumbers’ daily working lives, and maybe in the lives of sculptors and craft persons too. Shit happens.

David Archer’s sculptural works have been influenced by his interest in clay and in mechanical things. The appeal of the mechanical was reinforced by a coincidence in Archer’s life, when he was offered the opportunity “to restore and repair a genuine coin-operated amusement machine, a Bolland Brothers ‘Haunted House’…[and as a result] I was inspired to make large coin-operated cabinets, and made my own version of a haunted house”. This in turn stimulated David Archer to research the history of automata, which he has traced back as early as the ancient Egyptians. The fact that he chose to work with his plumber brother is therefore a logical extension of this long-term interest.

From the perspective of Rod–the-Plumber Archer, it seems that he is the kind of ‘decent Aussie bloke’ who simply enjoys assisting other people in realizing of their visions and aspirations. Having worked as a plumber for 25 years, in a variety of settings including construction, domestic, and high-rise locations, Rod Archer regards both functional and aesthetic elements as significant. Brother David describes Rod Archer as a ‘thinking plumber’. (Trades catalogue, 2008, page 8).

The Archer brothers’ scatological, mechanical pig sculpture wallowed in immense popularity for the entire lifespan of the Trades exhibition. Pearls Before Swine succeeded in attracting numerous punters beyond the art world’s ‘usual suspects’ and opening-night-attendees. No doubt in part the swine’s widespread appeal was in part a function of the work’s popular culture connections with fairgrounds and amusement parlours. Groups of mesmerized schoolchildren also gathered around the pig, possibly relishing its propinquity to, or commensurability with, playground ‘poo’ jokes.

In fact, Pearls Before Swine, along with the works co-created by the tattooist and the furniture maker, brought many people to this exhibition who had, almost certainly, never before entered an art gallery. Such audience development was an immense ‘plus’ for the Trades exhibition. It is no crime to make art accessible and certainly not a sin to be popular. The fact that a number of these co-authored works attracted different demographics and age groups should be seen as a real strength of this exhibition and therefore applauded. It happened because these works straddled various artistic disciplines and trades, and also, because a number of the works embraced or crossed over into popular culture. Attracting audiences beyond the ‘same old, same old’ Adelaide visual art aficionadi is not easy, and to do so without resorting to Damien Hirst or Jeff Koons-like populism, not to mention without the financial backing that underpins the success of such artworld luminaries, is rare. While the success of the Trades exhibition was on a more modest scale than that of such ‘big names’, in terms of its budget and scope audience responses to Trades were more than encouraging.

image

Collaboration between ceramicist Irianna Kanellopoulou and pastry chef Kirsten Tibballs

Ceramicist Irianna Kanellopoulou worked with pastry chef and chocolatier Kirsten Tibballs to create a delectable, although non-caloric sculptural installation of vividly coloured bunnies. Entitled Hopping Bertie and his friends, this artwork was fashioned largely from chocolate and vegetable dyes that seemed to have a similar consistency to Estapol. This (perhaps misleadingly) ‘edible art’ was another real audience sweetener.

image

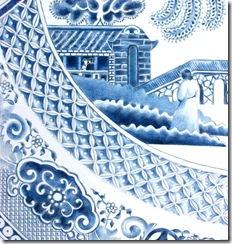

Collaboration between textile artist Annabelle Collett and electrician Jethro Adams

The artworks created by electrician Jethro Adams in partnership with textile artist Annabelle Collett were – well, electrifying. This team created two major works, the first a bright orange hammock, finger-knitted from plastic coated electrical wire, top-and-tailed by four light globes exuding a dazzlingly intense light. Electric Hammock also has a symbolic dimension, alluding to the chronic inability of members of our strung-out, high-powered society to relax in any truly meaningful way.

image

Collaboration between textile artist Annabelle Collett and electrician Jethro Adams

Collett professes a longstanding interest in what she describes as ‘crossover’ work and this was evident in the lighthearted, playful, electronic textiles on display in Trades. The Collett/Adams creative team’s edgy, wittily named installation, Mrs Tesla’s Dress, comprising white, knitted electrical cord, electrical components and globes, hanging from the ceiling of the exhibition space, simulated the ball gown of a glamorous lady. Ballooning out on the gallery floor into a full, although diaphanous skirt, its ‘hem’ was bedecked with generous-sized, rather hazardous-looking light globes. While perhaps a little dangerous as a form of daily apparel, Mrs T’s dress created quite a buzz and made a significant contribution to the Trades exhibition. (For the uninitiated, please note that a ‘tesla’, symbolized by the letter ‘T’, constitutes a standard measurement unit of magnetic flux density).

image

Collaboration between ceramicist Maria Parmenter and arborist Andrew Willsmore

Maria Parmenter, a respected Adelaide-based ceramicist, worked collaboratively with arborist Andrew Willsmore to create an installation of small, rather abstracted tree-shaped ceramic forms, entitled Utopia Avenue. This diverse row of miniature ceramic trees, not conforming to any single shape or colour, made for a fetching work. (DSC0022) In a second conceptual work, entitled Keep Safes, Parmenter made protective coverings for tree stumps. The latter work articulates with Parmenter’s previous work as a physiotherapist. Drawing an analogy between the missing limbs of humans and the arbitrary chopping down of trees, Parmenter remarked, “I’ve trained as a physio and I’ve worked with amputees. [In Australian society] we keep on lopping things off trees…and exposing stumps everywhere…I want to cover them up and [so] I’ve been making little caps for the stumps. Things to keep them warm.

image

Collaboration between ceramicist Maria Parmenter and arborist Andrew Willsmore

For Parmenter, the Trades project and exhibition also presented a unique opportunity – that of extending the interior world in which she habitually works as a ceramic artist – to embrace the exterior world that Andrew Willsmore inhabits on a daily basis.

image

Collaboration between glass artist Deb Jones and panel beater Hugh Gooden

Finally, panel beater Hugh Gooden worked with JamFactory glass artist Deb Jones to make contrastingly shiny, highly polished crumpled metal panels, exhibiting these alongside stripped, rusty panels, whilst installation artist Annalise Rees teamed up with carpenter Jonathan Bowles to create a large scale work using timber house frames covered by stretched organza, stitched with cotton thread.

To conclude, all of the participants in the Trades project and exhibition brought into being fresh, unique creations or artifacts wherein the sum was demonstrably greater than the contributing parts. Particularly in the creative partnerships between the Brothers Archer, and the Potter/Duncan, Adams/Collett and Clements/Bisetto teams, the emergence and materialization of a seemingly autonomous third ‘authorial’ hand, as signalled by Charles Green in his publication The Third Hand, became readily apparent. Where that “third hand” clearly emerged, spectators became genuinely excited about the artworks. It seems that perhaps a necessary pre-condition for this to occur is either for the participants to share a history of working together on a collaborative basis, or to have a pre-existing interest in each other’s line of trade.

Not all of the participants in Trades developed the same synergies or seamless merging of their differing skills and approaches, however. This is not necessarily a criticism of the quality of the work that any of the participants produced: it is simply a statement of fact that in some of these partnerships the approach of one party or the other emerged as the dominant one and this is reflected in the work. In others, the hands of both contributing parties were clearly evident. This too impeded the emergence of that third, transcendent hand.

Craftsouth, especially their Project Manager Niki Vouis, supported by the Director, Anne Robertson, are to be commended for envisioning, overseeing and administering this experimental project linking trades people with craft, design and visual arts practitioners. Equally, JamFactory Craft and Design should be acknowledged for its support for the project from its inception, through to the developmental stage and finally, for their successful hosting of the Trades exhibition, which was accompanied by a very professional catalogue with essays written by Kevin Murray and Mark Thomson as well as information about participants. Bold experimentation and fertile, co-operative partnerships of this kind are indispensable for the continuing health of Australian visual arts. The artistic future lies in this direction.

Reference

Green, Charles, 2001, The Third Hand: Collaboration in Art from Conceptualism to Postmodernism, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, U.S.A.

This is a feature article for World Sculpture News Hong Kong, Winter 2009

See also Symmetry: Crafts Meet Kindred Trades and Professions